Bright Beacon Blog

Click below to read my blog (newly arranged) covering topics on counselling theory and how it can relate to our everyday lives. The full blog and archive can now be found on Blogger at www.brightbeaconblog.blogspot.com

Feel free to comment and share. Thank you.

A very warm welcome back ever patient blog readers. Although imparting and receiving an education are both worthwhile and important activities, they don’t half take up a lot of time. Therefore, I apologise for the delay in producing posts.

Those of you that have been following will remember that I have been outlining the Ego defences as classified by Vaillant. The last post ended the examination of the Mature defences. I will, therefore, now pick up with the next ones on the list which are the Neurotic defences. These are often fairly common, and tend to appear at time of stress. If used long term can cause mood swings, relationship breakdowns and difficulties coping with stressful situations. They may also develop into the next level of defence. As with the Mature defences, I will break these defences into groups.

Intellectualisation: I have chosen to begin with this defence as it is one I will admit to using on a frequent basis (I write a theory based blog on counselling…who knew?). This defence allows us to move our attention away from painful or difficult emotions and onto cold clinical thinking. In physiological terms we move away from our amygdala and into our frontal cortex. While focussed on conscious, cognitive processing of an idea, we do not have to be involved with the emotions and feelings involved. For example, if I had to do a presentation, rather than facing the fact that I am nervous and worried about not being good enough, I might throw myself into learning facts and figures, studying the venue (there are thirty three steps to the podium) and the audience (there are representatives from five companies and I know what each one does), and rehearsing responses to potential (usually improbable) questions. This means that I do not have to face up to the fact that my Super-ego thinks I won’t be perfect, and my Id wants to run away in fear.

Intellectualisation can take the form of deep philosophical thinking, problem solving or sheer over-analysis. Thinking about things is acceptable to our Super-egos as society tends to reward thinking, and it allows us to ignore the demands of the Id. However, it means that the emptions are not being felt and processes and the psychic conflict and anxiety in the unconscious is simply being held off for another time. This defence is often common in the helping professions as it allows distance to be gained from troubling emotions when helping others, however, it blocks intimacy and empathy.

Rationalisation: This defence is related in a way to intellectualisation (siblings, cousins…hmm there I go intellectualising again). Whereas intellectualising allows us to escape from emotions into thinking, rationalisation allows us to escape into reasoning. This defence enables us to use excuses to rationalise our thoughts and behaviours, so that we do not need to take ownership or responsibility for them, and their associated emotions. Our Super-egos want us to be perfect and so if, and when we fail one way of preventing it from attacking the Ego is to blame something or someone else.

So if my presentation that I was nervous about was not a success I can rationalise away any disappointment I might feel by blaming the microphone, or the lighting, or the fact that it was after lunch, or the brief I was given was imprecise. In fact, the possibilities are endless, all that matters is that unconsciously I am able to defend my Ego from processing uncomfortable emotions. My Super-ego is satisfied by the deception as it appears to be logical and rational, and the Id is placated through justification for being uncertain at the start, or excused if it unconsciously caused unacceptable behaviour (e.g. storming off in a huff). However, by continually rationalising, the feelings are not being processed, and you are essentially denying responsibility. Twisting the truth can be exhausting and eventually things can catch up with you when the excuse pile gets too big to justify any more.

Dissociation: Dissociation has different levels. At one level it can simply describe a “switching off” from reality for a moment, for example when you are driving and get to a landmark and can’t recall the drive in between. This is known as highway dissociation. Daydreaming is another form of mild dissociation, when we check out from reality and enter our own thoughts and fantasies for a while. The Id will derive pleasure from this defence as it can allow us to be with our unconscious desires for a while. It may also include short periods of blanking out or disconnecting from ourselves, such as missing part of a conversation or momentarily not recognising ourselves in a mirror. These can sometimes occur during times of tiredness or stress, as a defence. By disconnecting and dissociating we do not have to engage with thoughts and emotions that could cause us distress, and therefore they defend the Ego. At this level dissociation can be described as acting as a Neurotic defence mechanism. So, if while I am waiting to go on stage to deliver my presentation, I may drift off to imagine a rapturous round of applause and standing ovation at the end, which I am only pulled away when someone taps me on the shoulder. This would be me dissociating rom my feelings of nervousness and anxiety.

However, dissociation can be far more severe and develop into a pathological disorders. This can be caused by sudden large, or ongoing trauma. As we move along the dissociation spectrum, there are disorders such as depersonalisation, where one feels detached and separate from your own body. Derealisation, where the world doesn’t seem to be artificial, and amnesia where memories are detached and forgotten, and fugue states and personality dissociated identity disorders, where aspects of personality are split off or new personalities developed. These are complex conditions which require specialist help to manage and provide care for. I will not go further into them, but I will highlight the organisation Positive Outcomes for Dissociative Survivors (PODS) https://www.pods-online.org.uk/ which has information and resources about dissociation and its associated disorders and support.

Repression: Repression can be seen as an extension on some of the Mature defences outlined previously. In thought suppression and distraction, troubling thoughts and emotions were essentially pushed to one side to allow normal day to day functioning, but were then picked up again for processing later. In repression, however, the thoughts and emotions are deemed unacceptable (usually by the Super-ego) or are too painful to face, and so they are pushed down into our unconscious. Memories of difficult situations and emotions are pushed down and buried in the hopes that they will disappear. This can be done by the Ego in two ways. It can exclude things from conscious thought before it gets there. In other words, a terrible event happens, but it is so traumatic that its content (emotions and memories) are pushed into the unconscious before you’ve even processed and thought about what has happened. The other way is to repress the problematic content afterwards.

The problem with repressing emotions and memories is that they do not go away, instead they linger in our unconscious. With the right triggers, they can then remerge through our pre-conscious and into our conscious awareness. So for example, I may have repressed memories about a previous terrible presentation that I gave when I was much younger. I am not even aware of it as I am waiting to go onstage. Then I see something, for example the shape of the podium, and I start to recall the event and feelings from before, and I become overwhelmed with feelings of fear that were repressed.

As with dissociation, repression can exist on a spectrum. Some things that we repress may simply cause us mild discomfort and distress, however, deeply traumatic events can cause major repression which can remain hidden for years, only to come out later.

I will leave it there, having looked at the first four of the Neurotic defences. I hope it can be seen how these are a step up from the Mature ones in terms of how they operate, and the effect that they can have when they are employed.

Hello, and welcome back to my Blog. The title of this post might suggest I am wondering off topic and onto the complex world of cheese. Unfortunately, or fortunately (you decide) it actually refers to my continued exploration of the Mature Ego defences suggested by the Freuds and others. If you recall, these defences can be used in a semi-conscious (still my term) way, and allow us to defend our Egos from difficult emotions in a more constructive and “healthy” way. Although, I would still caution that their over use may be cause for concern. So, the next on our list is:

Distraction: As the name suggests, this is when we consciously put off thinking or feeling about a particular issue, thing or person by refocussing our attention onto another activity. From this description, it might sound similar to sublimation which was mentioned in my last post. The difference, however, is that in sublimation there was a use of the psychic energy from the emotion for another end, by rechannelling it onto another activity. In this defence, literally any activity at all is chosen as a way of diverting our attention away from what is troubling us. So for example, if I am feeling sad about having broken something, I might chose to watch my favourite TV programme so that I am not thinking about it anymore. The programme is not being used as a way of making me feel better, it is simply acting as a metaphorically shiny thing to distract your mind away from the difficult emotion or thought that it doesn’t want to feel or think at that moment. Another example might be to read a book rather than sitting feeling anxious and worrying about an upcoming test. The though or feeling doesn’t go away, and in fact, you cannot keep yourself distracted indefinitely, but what it does do is manage when and where you might have to deal with the issue. It is also managing to keep the Super-ego and Id distracted and busy, so that your Ego can perhaps ready itself for their combined onslaught. It is a delaying tactic to hold off the inevitable, but it can be what is needed to help you function.

Thought suppression: Like distraction, this Ego defence is used to delay the processing of thoughts. Rather than using activity, it uses our force of will to push unwanted thoughts out of our awareness. It is a bit like our minds putting its fingers in its ears (!) and singing “la la la la, can’t hear you” to any thoughts that might be distressing us. It is a voluntary (as it is partially in our conscious) version of the neurotic defence of repression. The difference is that you are more aware that it is happening and so it is temporary in nature. Like distraction, it is useful for holding our Super-egos and Ids at bay perhaps until our Egos are in a better or more appropriate place to process the troubling thoughts. For example, you might receive a parking fine, just before you are going to a meeting. You might say to yourself, “I haven’t got time to deal with this now, I’ll think about how I’m going to pay for it later”. You will then push the thought out of your awareness so that you can concentrate on your meeting. Later, however, you will have to consciously reengage with the thought of how you are going to pay the fine.

Another issue with this defence is that sometimes our ability to suppress a thought may not be a strong as we think. Our Ids and Super-egos are pretty tough, and so what can sometimes happen is that the thought sneaks back in when we are least expecting. For example, you are halfway through your presentation, someone has asked a really key question and your mind goes blank. All your brain can access it the thought of the fine sitting on your desk. Thoughts also trigger emotions and so there is often a leaking effect with this defence, and the emotions associate with the thought might find themselves leaking out. In the example with the fine, you might find yourself feeling a little bit angry with people in the meeting as this is how the thought has left you feeling. Sometimes a thought may cause sadness and this may cause tearing up in an inopportune moment. Verbally, your unconscious might cause a Freudian slip to let the true thought leak out. For example you are talking about securing funds for a project and you end up saying, “I’m sure we will be able to get the fines we need for that to go ahead. This is perhaps a defence to use sparingly, as it is not necessarily the most reliable.

Anticipation: Unlike the tense waiting for something suggested by Frank-N-Furter I Rocky Horror, this Ego defence is all about using waiting time to plan, in a sensible and realistic way. When we know something unpleasant is going to happen, the suspense can cause us a lot of emotional distress, as we worry and ruminate over all of the possibilities. Our Super-ego takes advantage of this time to remind us of our failings and mistakes and tell us that we will have to respond perfectly. Our Id bombards us with images of failure and destruction from the Thanatos (death drive). In order to protect itself, what the Ego can do, is to get a little perspective and rationally form a plan of action. Using all of the available information it can prepare for the worst (and try to expect the best). This uses the psychic energy in a more constructive manner than simply worrying about what might go wrong (so there is a little similarity with sublimation, but this is usually through thought, rather than action). So for example, you have sent an application form in for a job and you are waiting for a reply, rather than worrying and feeling anxious about what the reply might be, you can instead plan for how you will handle yourself in the interview, if you are invited in for one. You can also plan for which other companies you can apply for, if the response if a no. Your Ego is managing to placate the Super-ego by doing something constructive and sensible, while you are reminding the Id that you live in the real world, and not the fantasy one constructed from its whims.

I like to think that this defence has echoes in Transactional Analysis, as the Adult Ego State will respond to stresses and concerns by taking a rational approach to the problem. This is done using the physical, intellectual and emotional information available to it, to come up with a plan. This means that you are not slipping into distressing feelings that perhaps you are not fulfilling your drivers (from your Parent Ego State), and you are also not sinking into the Injunctions given to you as a child (and felt by your Child Ego State). A key point to note in this defence is that the planning must be realistic. It cannot be driven by fantasy, which can be difficult to do, due to our brain’s excellent talent of using imagination to fill in the blanks (see previous Blog Post).

Introjections: This Ego defence appears to have some similarities to identification. It is when a person takes on aspects of personality, beliefs and ideas of another person. This is usually a caregiver when we are growing up. We absorb these attitudes without thinking and automatically. For example, we might take on our parent’s views on gender, religion, politics and race. These often inform our values. This happens unconsciously and through the authoritative nature of the caregiver to us. It can also occur with other authority figures such as older siblings, teachers, grandparents etc.

The reason that it can be used as a defence is that if we take on values that are positive, for example kindness, thoughtfulness, compassion, responsibility and loyalty, we can use these in our relationships with other to achieve positive outcomes. As a child, these more positive attributes from a caregiver that were taken into ourselves allow us to cope when that person is not there. We can use the compassion of a parent, for example, to self-soothe ourselves if the parent is not present, as it is inside of us. We can kind of have the person’s voice internalised in our thoughts to act as a useful guide when we need it. These introjected aspects are useful tools in the managing of the Super-ego / Id conflict with in us.

The problem with this defence is that not all of the aspects we take into ourselves may be positive. So we may form values that are at odds with the majority of society. We may also take the introjections to form our sense of ourselves and be left with feeling unworthy. There is a comparison to be made with these negative introjections and the injunctions from TA, which are messages given from childhood which negatively impact our view of ourselves and our development. There can also be a cognitive and emotional dissonance if we introject a part of someone else that we then later find out is not true. So for example, we may idealise a parent for their strong morals and loyalty, and then later find out they had an affair. Abuse of any kind, sets up damaging systems of introjections as well, which are immensely unhealthy. Therefore, this is a defence mechanism which although has many positive aspects (which is why it was considered mature by Freud), it is definitely a double edged sword in terms of the impact that it can have.

So there we have the mature Ego defences. I hope that it has been clear how they are able to keep us safe from the struggle between the Id and Super-ego, and how at this level, they are largely helpful, healthy and above all socially acceptable. Remember, we all have them, but these ones might be easier to spot in ourselves, due to their nature crossing into our conscious awareness more often. You might like to see which ones you have a preference for, and when you employ different ones. This type of self-awareness can be useful to allow us to better defend ourselves emotionally, should we need to.

Welcome back to the wonderful world of ego defence. Last time I described how Vaillant categorised ego defences into four groups: pathological, immature, neurotic and mature. Over the next two posts, I want to look at the mature defences in more detail.

The mature defences are used on a day to day basis by most people. Unlike the other levels they operate on a semi-conscious (my term) level. In other words, sometimes we can engage them through conscious thought on a voluntary basis. However, if we habitually use certain ones we might really be aware of what we are doing, and so they are operating just outside of our awareness. This in contrast to the defences at the other levels operate unconsciously.

Mature ego defences allow us to function in society and can allow us to have successful relationships and interactions with people. In this way, they can be helpful to both ourselves and society. However, it can be argued that if they are used to an extreme level they may start to have negative effect or transform into other defences or behaviours. I will outline some of them and how they might operate to protect our Egos from our Ids and Super-egos.

Humour: I have chosen this defence to begin with as it is a common one, and one I use personally. It should be noted that not all humour is a defensive response. However, humour is a useful way of coping with difficult thoughts and emotions. There is the old cliché about the “tears of a clown”, suggesting that behind their happy exteriors, clowns are really crying and sad on the inside. There may be some truth to this. This is because sometimes there is truth in a joke or humours remark. When this occurs it shows how humour operates defensively. It enables us to express something that is painful or distressing to us whilst giving pleasure to those around us. So making a joke about missing the bus enables us to let people know that we are a bit gutted about it, without us having to explicitly acknowledge it. We can successfully negotiate around the difficult feeling, while still having implicitly expressed it. This is useful in society, as other people will not then feel they have to engage with the difficult emotion that is perhaps behind the joke.

One way in that humour is used in this way is through self-deprecation. If we make a mistake, this can sometimes cause us disappointment, shame, resentment, guilt, or any of a host of other emotions. If another person highlights the mistake, they may put you in a position where you have to publicly acknowledge it, and then deal with the feelings directly. So a way of circumventing this is to make light of the mistake with a joke or comment. You are externally owning the mistake, without having to deal with the difficult emotions. You have therefore allowed you Ego to by-pass the judgement from the Super-ego which is striving for perfection, and also placated the Id which might want to lash out in anger or despair.

Identification: I am going to suggest that this ego defence (as with most things, including the other defences) operates on a wide spectrum. It was originally identified by Feud as identification with the aggressor, and was linked with his idea of the Oedipus complex (which I am SO not going into here). Essentially, it suggests that in order to cope with and resolve feelings of fear caused by another person, we can start to identify with and then behave like they do. This imitation will then endear us to the threatening person so that they will accept us. We engage in this adaptive behaviour when entering strange situations, for examples starting a new job. One thing we might do is start to act I the same way as our colleagues as a way to gain their acceptance. Our Super-ego will be content as we are following the social norms of the environment, and our Id doesn’t need to act out of fear from threat, ostracization and rejection. This defence allows us to operate well in society and be successful.

However, I would argue that there can be a point at which we adapt too much to fit in, and can perhaps lose some our authenticity, which might prove to be harmful in the long term. There is also an extreme form of identification, which is Stockholm syndrome. This is when someone who is abused, kidnapped or mistreated, and in order to survive they adapt in such a way that they completely identify with their captors and persecutors, becoming just like them, and even feeling sympathy and allegiance with them. These positive bonds can be exceptionally strong, and only when out of the harmful situation does the people fully feel the traumatic effect of their ordeals. Obviously, this is extreme, and I hope you can see it is removed from the mature utilisation of identification.

Sublimation: This defences was one originally suggested by Freud and has strong links with the Id. Sublimation is essentially the refocussing of energy from a drive or impulse that is perhaps harmful or socially unacceptable, into something more positive. For example, we may be exceptionally angry with someone, but rather than tapping into our Ids need to lash out in a destructive manner, we might chose to use that energy in another pursuit. These activities could be anything, but are often creative or active e.g. painting, singing, running, playing sports, making a model, or tidying the house. So if I was really sad and my Id just wanted me to sit and eat ice cream to fulfil my need for comfort, I might sit and write a poem about my feelings instead. The Id is calmed, as the energy has been utilised and not stored up, and the Super-ego is ok as you are doing something productive with the energy. Your ego is protected from them both and has not had to process the emotion directly. You can also see how this can be a positive defence to use, as you are doing something of benefit to yourself, and possibly those around you. You can possibly think of all the wonderful things that have been created, and the great accomplishments achieved by people who have perhaps been sublimating their difficult emotions. As with all these defences, however, if over used it may mean that difficult feelings are never being processed fully and so there will be some harmful build up over time (consider those creative people who have been depressed).

Altruism: This defence is one that tends to utilise our empathy. It has been suggests that as a social species, empathy evolved as a way to allow us to interact with members of our society in more productive ways. We are less likely to do harm to others if we can put ourselves in their position and imagine what it would feel like for them to be hurt. What behaving altruistically allows us to do is to help others who may be feeling what we are feeling. This means that we perhaps don’t have to process an emotion head on, but instead do it in a more vicarious way through others. So for example, if I have been recently bereaved, I might decide to help out with a charity for bereaved children. They are likely to know how I am feeling, and I can hopefully alleviate some of their grief. If I have just come out of a long term relationship, I might offer to help out a pet rescue centre, as I can identify with the animal’s perceived feelings of abandonment. This Ego defence, definitely supplicates the Super-ego, as it is about giving back to society. It also allows the Id to feel connection with others and so link to the Eros (drive for life). I would offer that although this defence seems completely positive, there might be a link with TA drivers in terms of ‘Please me’ and so it is important to make sure that the defence is not employed so much that your own needs are not addressed.

Next time, I will continue with the rest of the mature Ego defences…

Hello once again to my look at some aspects of psychodynamic counselling theory. Last time, I went through an outline of Freud’s model of psychic structure, which was composed of the Super-ego, Ego and Id. I want to now start to look at the Ego Defences associated with this model.

The term Ego Defence suggests that the Ego needs to defend itself against something. If the look at the structural model of the psyche, the poor Ego is stuck in the middle of the Super-ego and the Id, which are both in conflict all the time. The Id wants all of its needs supplied, now if possible. Meanwhile, the Super-rog is constantly pointing out why these needs should not be fulfilled, and how they are against the aim of achieving perfection. The Ego has to act as the moderator between these two warring factions and this is can be exhausting. Freud suggested that managing this conflicts leads to anxiety. This can include feelings of guilt or shame, which can lead to emotion states such as extreme sadness and depression. So in order to survive this ordeal, we develop a set of defences to allow us to function while by-passing the feelings from the Id and Super-ego demands. These are our Ego Defences, and they operate on an unconscious level. This means that unless we engage I some serious reflection, we do not know we are using them. Even after they are in our awareness, they still operate in the moment, from an unconscious place.

Sigmund Freud originally came up with a set of around five main defences, and his daughter Anna then further defined these and added to their number. Later theorists have further expanded the list. George Vaillant devised a categorisation system for the Ego Defences, which is based on their stage of development and association to personality disorders. This system was one of the key foundations of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, now on its fifth edition).

Vaillant suggested four levels of defence, which I will go through in reverse order (as this is how I will look at them in subsequent posts):

Level 4, Mature: These are defences that will have been formed in childhood, but are extremely common in adulthood. They allow an individual to defend their Ego, while allowing full functioning in society. They can be considered “healthy” defences, as they are unlikely to lead to too many social problems, unless used to excess, or they develop into later level defences. Examples in this level include, humour, altruism and anticipation.

Level 3, Neurotic: Again, these will have formed in childhood, however, if utilised can cause breakdowns in relationships over the long term. They are extremely common in adulthood, as they provide a means of coping with stresses in the short-term. People that use these as their primary defences may find some aspects of life difficult. Examples in this level include, intellectualisation, repression and displacement

Level 2, Immature: As the name suggests, these defences were formed at a very early age. If these are used, other people often find them difficult to handle or deal with. They are less common than the previous levels, and may only appear in times of more extreme stress. Due to their anti-social nature, they can cause difficulties in life if used regularly, and are often associated with personality disorders, high levels of anxiety, and long term depression. Examples in this level include, acting out, passive aggression and hypochondriasis.

Level 1, Psychotic or Pathological: These are extreme defences in which the Ego actively rearranges or warps reality. They can form as responses to trauma, where to face the actually reality might be too damaging. They often appear to be highly irrational and “crazy” to other people, and for this reason, they can have a highly disruptive effect on a person’s ability to function in society. Due to their unconscious nature thy can be the cause of disturbing dreams and nightmares. Examples of these include, delusions, distortions and extreme denial.

So if those are the different levels of Ego Defence, how might they present themselves in real-life? Imagine as an example you have accidentally picked up someone else’s item from a shop counter as well as your own. At this moment your Id might be feeling really happy with the unexpected gain and be demanding that you keep the item and leg it out of there. At the same time, your Super-ego will start to berate you for having made such a stupid error. It will also point out all the horrible consequences of keeping the item and imagine what others are thinking about you. At this moment of internal conflict, the Ego needs to protect itself, even if it has consciously decided to return the item to the cashier.

In a mature way, you might take the item back and utilise humour in a self-deprecating way. Perhaps you would say something like, “So sorry, I took this by accident. What a ding-bat!” This response will enable to brush off the attacks from the Super-ego, by allowing perceived criticism from others to be ignored, as you’ve told the world how stupid you are.

In a neurotic way, you might take the item back, but internally run through all the reasons why it was not your fault, why it would be silly to keep it, and why no one is thinking any less of you. You might argue to yourself that if it hadn’t been so close to your stuff you’d never have picked it up. The colour of the two items was so similar that no wonder you thought they were just one thing. People do this kind of things all the time, and besides, you were talking to the cashier, and so that must have had some role in distracting you. It would be daft to keep the item as well, as it’s not even something you would use, and it would be silly getting into trouble for something so small. I this way, you are able to keep the Id supressed as you are explaining away why it can have the item. You are also providing the Super-ego with rational reasons why you shouldn’t feel any guilt.

An immature response might be to take the item back, but passively aggressively place the blame on the cashier. You might say, “I had to bring this back. Someone placed it near my items, so it found its way into my bag”. The message here is clearly that the accident was not your fault, and that therefore you can silence your Super-ego by shifting it elsewhere. You are also not being overtly rude or aggressive and so your Super-ego cannot complain about anti-social behaviour. The aggression (in the passive aggression) will provide a useful emotional outlet for the Id which wants to express its annoyance at not being able to keep the item.

A neurotic response might be to see the item and believe that someone has purposely placed it in your bag. They are now watching you through CCTV to see what you are going to do. There is a squad of armed security people waiting behind a door, ready to pounce the moment that you reach the exit to the shop. With this response you might run back to the cashier with the item, drop it on the counter and run off as fast as you can.

I understand that the example might be a bit silly, but hopefully it shows you in some way. How Ego Defences operate. I am also aware that I have somewhat personified the Super-ego and the Id. This is simply to illustrate ow they are in conflict and I am not suggesting that there are literally a set of voices having an exchange in your head. In fact due to their unconscious nature, most of what I described above would happen I a few seconds and without you even being aware.

What I plan to do over the next few weeks or month is to go through sets of Ego Defences and describe what they are and how they function to protect our hard working Egos.

As my first proper post of 2019 I thought I would start with something light and fluffy… who am I kidding, no I thought I’d have a go at explaining Freud’s theories on the mind and psychic structure. Most people have heard of Sigmund Freud and know that he had a major impact on the world of psychology and was the father of psychoanalysis.

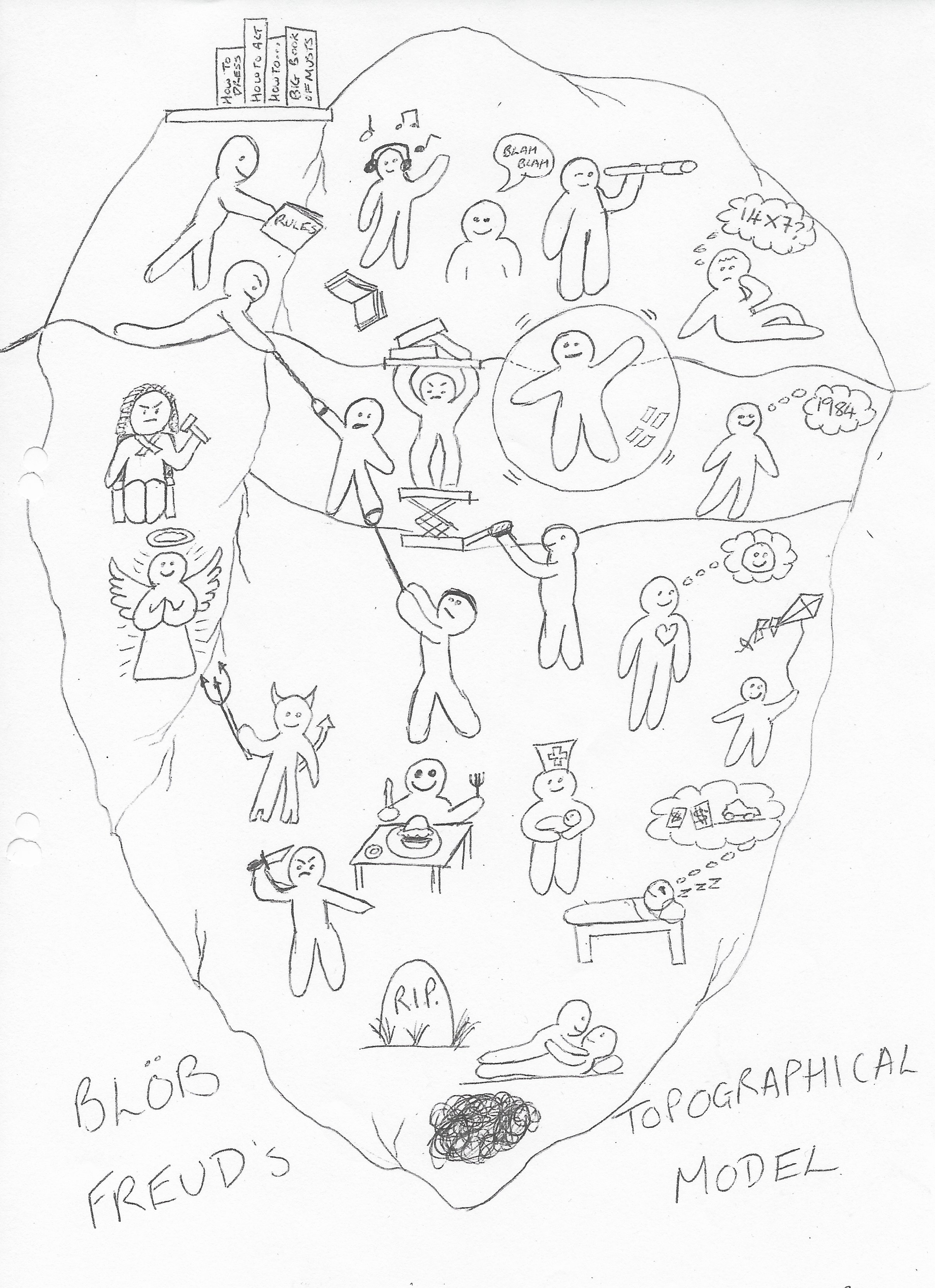

A fundamental part of his ideas is how he saw that the mind is structurally organised. This organisation doesn’t link particular processes to physical parts of the brain, but instead outlines ways in which our mind works in a theoretical way. He suggested there were three main structural domains of consciousness: the conscious, the pre-conscious and the unconscious (please note that he did not use the term sub-conscious, and I will not either).

Conscious

The conscious part of our mind is where our thinking and perceptions of the world occur; and is fully in our awareness. I know what happens in my conscious mind and it uses my attention. I can draw my attention to, and become consciously aware of my senses. I am using my conscious mind to write this sentence for example. I can also consciously stop and plan what I am going to be having for dinner.

Preconscious

The preconscious is interesting in that things here are not in our awareness, but they are accessible to us. It acts a little bit like a holding facility for our knowledge and memories. If we are lucky, we can retrieve what we need and bring it into our conscious mind. It can however be a little bit unpredictable and unreliable at times. For example, when you are trying to think of a particular word or name and it ends up on the tip of your tongue, and just out of reach of your conscious mind’s grasp. Or when you have the lyrics of a decades old song floating around your head instead of the figures for your important meeting.

Unconscious

The final domain is the unconscious. This is packed to the brim with all of the things that go on out of our awareness. It is interesting that many psychologists argue that the unconscious doesn’t exist, and prefer to relabel things that happen in our brains without our awareness as automatic or autonomous. In this way, it can include autonomous processes such as breathing, our heart beating, and reflex responses. It is impossible to measure the unconscious (as we aren’t aware of it!). For this reason it can be considered as a theoretical concept, rather than an actuality.

The unconscious makes up the largest part of our mind’s structure, and recent research has suggested that even more of our processing happens in the unconscious realm than we first thought. Freud suggested that rather than processes as such, our unconscious is filled with urges and drives that are out of our awareness, and cannot readily come into our awareness (without a lot of work and perhaps therapy). Earlier, I consciously thought about what I would be having for dinner, but I was not consciously aware of how hungry I was up until that point, and I am also not sure why I am craving prawn cocktail crisps.

To make this structure clearer he proposed a topographical way of looking at it, which we can compare to an iceberg. Icebergs are visible at the surface of the water, but most of their mass is hidden underneath. The same is true of our psyche. The conscious forms the tip which is sticking out, the preconscious exists on that boundary with the waves covering and exposing different parts at different times, and the unconscious is everything underneath.

Freud then suggested that our psyche is composed of three psychic components; the id, the super-ego and the ego.

Id

The Id is a completely unconscious part of the psyche. Freud suggested that it is present at birth, and emphasised its high level of control over our thoughts and behaviours. The Id is composed of all of our most basic and primitive instincts and drives. These can include our fears, needs, irrational wishes, sexual desires, fantasies, immoral and unacceptable thoughts, and violent urges. It also houses our shameful and traumatic experiences (which may have been repressed from our conscious mind). Many of these can be divided into two drives which Freud called Thanatos and Eros. Thanatos is the death drive, and so would include desires to harm others or ourselves in some way. Eros is the drive for life, and so would include desires for love, intimacy, sex and passion for life. (I may write a post on these drives in the future to give more detail).

The Id exists to fulfil the pleasure principal. It wants what it wants, and it will try and do whatever it can to get fulfilment. This is a useful thing to be born with as it drives a new born to seek out things like food, water, warmth and attention from a caregiver. As the infant grows, however, and parents exert their influence many of these urges become unacceptable, certainly to the community that the child is living in. Someone who is completely Id driven will simply act on impulse without conscious thought or consideration for others, simply living to fulfil its own needs (which may ultimately include death).

Super-ego

I have chosen to look at this aspect next, as it is in contrast to the Id. Whereas the Id is completely in the unconscious, the Super-ego has a small part that is conscious in nature and can cross the preconscious. It develops after the Id from our interactions with the world, and especially our primary caregivers. If forms in response to the rules, expectations and guidance we are given by external forces. Due to this it aims to prohibit and quell the desires and impulses of the Id. In this way, the child can behave and function in a socially acceptable manner. The way it exerts its control is usually through the tools of shame and guilt. So, my Id might want instant gratification by wolfing down a (or several) bag(s) of prawn cocktail crisps, my Super-ego would be reminding me that I might be seen as being a glutton, and that I will get fat and that I’m a bad person for wanting to eat something so unhealthy (especially after I have done it).

The Super-ego is running on the principal of perfection. It is striving to guide a person towards our ideals and to behave in line with our values and conscience. Someone with a very strong Super-ego would be rigid in their thinking and behaviour, and also be exceptionally self-critical and judgemental, possibly to the point of self-destruction.

Ego

The use of the term Ego proposed by Freud is not the same as the use in common parlance. So where as someone might be described as being egotistical or having a massive ego to mean they are full of themselves or have exceptionally high self-esteem., this is not what Freud was referring to. He theorised that the Ego is the part of us that develops throughout child hood to act as a mediator between the Id and Super-ego, which are constantly in conflict. It perfectly crosses the conscious and unconscious (or floats between the two), with many of its processes occurring in awareness. It acts on the reality principal. In this way it seeks to use functions such as judgment, planning, experimentation, learning, remembering, and organising to make sense of the world. In doing so, it is able to provide for the needs of the Id in the most acceptable way, therefore also placating the Super-ego in the process. Some have described the ego in terms of common sense and reasonableness. It develops as we learn about the world through our experiences and relationships with others. So my Ego was able to remind Id that I would be having dinner soon and so I would not be able to have crisp, but I would also not be hungry. I will be eating just enough food, and so my Super-ego doesn’t need to make me feel guilty for my behaviour.

A person with a well-developed ego will have a good sense of themselves, their values and drives, and be able to moderate these in order to function effectively on a day to day basis. They will be able to withstand the conflict between the passions and urges of the Id and the criticism and judgement of the Super-ego. They will not fall prey to the anxiety caused by responding to every Id driven impulse, or the guilt, shame and anxiety handed out by the Super-ego for failing to achieve perfection.

I hope from this brief overview that you can see how Freud viewed our psyche as operating to determine our personalities and behaviours. Those of you that have read pervious blog posts will also be able to draw parallels between this psychic structure and the Ego State model proposed in Transactional Analysis. Although not the same, it can be argued that the Parent Ego sate is similar to the Super-ego in that it can aim to control behaviour through rules and expectations, rewards and punishments. Aspects of the Child Ego state, especially the Free Child, reflect the Id’s desire for pleasure and enjoyment in life. The Adult Ego state has a moderating function similar to the Ego, which is based on an objective evaluation of reality to best provide for a person’s needs.

I hope that I have also shown the importance of a well formed Ego in being able to manage the conflicts and demands of the ID and Super-ego. In much the same way that Transactional Analysis aims to strengthen a person’s Adult Ego state, psychodynamic approaches to therapy can explore a person’s Ego and try to bring some of the unconscious aspects of the Super-ego and Id into awareness. In this way, the Ego is better prepared to manage them and respond in a different way.

Over the next few weeks and months, I want to use this blog to look at a way in which the Ego is able to protect itself from the battle of the Id and Super-ego through utilising processes called Ego Defences.

Happy New Year to all of you reading this blog. I realise that it is a few days late, but hopefully the sentiments are not lost. I realise that it has been a fair few months (five?) since I have last posted on this blog. This has been due to losing a bit of balance in my life between working, studying and generally sorting stuff out.

There have been more than a few studies suggesting that making New Year’s resolutions is not a wonderful way to make changes, and most tend to be broken well before the end of January. Instead, I am treating this period of time as a bit of a fresh start and a time to re-evaluate what needs doing, and what is important. I have missed writing blog posts and would like to do more of it in 2019.

Therefore, rather than a resolution, I would like to propose an ambition to work towards of posting at least two posts per month to this blog. The feedback I have had has been positive and really encouraging, and I have nothing but gratitude to the people that chose to read what I have written, so I hope that I will be able to fulfil my ambition, and that what I produce is useful to you. Please let me know if you have any feedback or comment, or even suggestions for anything that you might like me to write about. This year, I am going to leave Transactional Analysis for a little bit (I will return, don’t worry), and instead have a look at some aspects of psychodynamic theory.

Anyway, thank you once again to anyone that follows this blog, your support is really valued by me, and here’s to a happy and successful 2019 to each and every one of you. Hopefully you will be able to progress well on any of your life ambitions.

Have you ever felt a feeling of being torn apart from within, or by being completely confused or overwhelmed by your thoughts and feelings? If so, then it is possible that it is being caused by your injunctions and drivers. In my last post, I summarised the injunctions and drivers of TA. I want to move on to look at how they interact, and what the alternative to them would be.

The analogy I am going to use is that of a person at sea on their own. This is not an analogy of my own making, and unfortunately I cannot credit the original source, but I have seen it used by Adrienne Lee. So imagine if you will, a person, floating out at sea, with nothing else around them. The sea represents life. We can imagine that the person has been dropped out of nowhere, into this vast sea of life. Naturally, the person will float, as babies tend to when they are born. What happens however, is that other people come along to support and help the person. As they do so, things become attached to the person. Some people attach weights of varying heaviness to the person’s legs. It starts to pull them under the water. It takes more and more effort for the person to try and stay afloat. These weights may have been given as a condition of support and help being provided. In this way, they represent the injunctions placed on us by caregivers. If this was all the person was given, then fairly soon, they would sink and sadly drown in the sea of life.

Some people when they give their assistance also provide a gift of a large helium filled balloon, which they tie around the hands of the person. These start to lift the person out of the water. If many are given, the person may start to rise up out of the water. This is a precarious position to be in. The wind might carry them off, they have no control, and the balloons might burst at any moment. This would send them crashing down into the water. These balloons are like the drivers, given as life lessons to the person when help is provided.

From the analogy you can see that drivers (balloons) area able to counter the effects of the injunctions (weights), and this is why very often, driver behaviour is employed by people in the grip of the negative emotions caused by injunctions. They can be a survival mechanism. The problem with drivers, however, is that they are nearly impossible to control, and their effects cannot be maintained. It doesn’t take much to burst the balloon. It might be making a “silly errors”, if you have a Be Perfect driver, or it might be working yourself to exhaustion so that you cannot carry on if you have a Try Hard driver. When the balloon pops, you go crashing down into those emotions caused by the injunctions, eventually sinking under the water. The crash itself might cause harm or be deadly, depending on how high you had gone. You might try desperately to blow the balloon up again to help it pull you up again, but the effort this takes is enormous.

In this way, living life according to your injunctions and drivers (scripts, anti-scripts and counter-scripts – more on this in a later post) is not a pleasant prospect. You drivers and injunctions are continually pulling you in opposite directions. You might feel the effects of being steady on the surface, but this is an illusion. Imagine the effects it is having on your poor legs and arms having to bear the load from the top and bottom. Some people constantly try and inflate their balloons, or perhaps more rarely add more weights (these might be added by unforeseen events or occasions cause from driver behaviour) to balance themselves out. The result however is the same pulled feeling and continuous strain. This same strain is caused by the drivers and injunctions causing a flip flopping from negative parent to negative child ego states. This is also an exceptionally stuck position. The person is not free to move where they want to. They are exceptionally prone to be moved by the waves and the tides that life throws at them, or they are left to float and never reach a destination.

Hopefully, having rad my previous posts, you will be able to see what needs to be done about this situation. Rather than filling up the balloons to counteract the weights, it is possible to give yourself permission to take them off your legs and let them sink off slowly to the bottom of the sea, and away from you. Rather than letting the balloons carry you off on the winds into the scary heights above, you can choose to let them go, preferring to make your own decisions, rather than following prescribed and handed down sets of rules.

In this way, you are making a choice to be autonomous and authentic. This person who has not weights or balloons is an authentic adult, living and responding in the here and now from their adult ego state. They are free to make their own choice to swim in which ever direct they chose, comfortable in the knowledge that should they stop, they are able to float on their own. The drivers (balloons) are pulling towards a sense of perfection (always on time, always strong, always kind, and always working) and the injunctions (weights) are constant discounts, reminding you of perceived unworthiness and failure. The free floating lack of these can be considered the “good enough” or “OK” position. It is neither perfect, nor unworthy. It is a position that is accepting of its flaws and imperfections, but is also proud and acknowledging of its achievements. A person in this position will strive to reach goals (swim to an island?) but will be ok to take a break, ask for help or change course if they need to. This is an amazing place to be in. It might be impossible, but remember, a person can still do some swimming even with a few small weights on their legs and perhaps one balloon on a wrist. The more we remove, the easier things become.

I hope that this analogy has been some help in understanding how the drivers and injections can operate together, and what it might look and feel like to live without them. In future posts I aim to look in more detail at the “OK” position in respect to how we live our lives with others, and also how we form scripts about or lives. Until next time, remember you have PERMISSION to remove weights, and the CHOICE to let go of balloons….

After a pretty long break, where I have given myself permission to be busy with work, raining and having a holiday, I am back to continue with my blog posts.

I feel the break happened at a fairly natural point, having completed my description of the major injunctions of the Transactional Analysis theory. Things however, are not fully complete on this front. In this post, I want to discuss briefly some additional injunctions and then give a summary of drivers and injunctions.

All theories in the natural and social sciences will grow and change over time based on new evidence and research that is done. Later theorists will also offer up their ideas and perspectives. I have therefore found some additional injunctions which have been postulated. I will only discuss them briefly as most are simply extensions or subsets of the major ones which I have already covered in previous posts:

Don’t Trust: I mentioned this injunction briefly as being a subset of ‘don’t be close’. It comes about from the message being given that people are not to be trusted and therefore you should not form relationships with them. This is usual based on fear (if you remember from the caregiver’s child ego state) that the child will get hurt if they get close to others. It can also be formed from parents who are exceptionally inconsistent in their approach. If a child cannot be sure they will get their needs met from the people they have to rely on, then they come to mistrust not only them, but everyone else. Often this can also include themselves. In adult life this might show itself through strong independence and a paranoia around others, perhaps even imposed isolation.

Don’t take care of yourself: This can be seen as an extension of ‘don’t be sane/well’. That injunction provided the message that needs only get met if you demonstrate some kind of imperfection of inadequacy. Once this is done, the caregiver will provide for your needs and give you attention. In the same way, a child can be given the message, especially from parents who are continually in their negative nurturing parent ego state, that they are incapable of taking care of themselves, or unworthy of this care. They form the belief that care must be provided by others, and under the conditions that the other person imposes. In adult life this might manifest as a reliance on support from others and society, and a complete negligence of basic self-care.

Don’t Want / Need: This can be viewed as a subset of ‘don’t be important’ which imparts the idea that as a person you are unworthy to have your needs and wants met. ‘Don’t want or need’ can be given as a message directly to a child by telling them they are too demanding, or implying that what they are asking for is unreasonable in some way (when in fact it probably is not). There will not be a reasoned explanation given as to why something cannot be given (e.g. not money) rather the perception the child will have is that there is something wrong with them and their desires. I adult life this is shown by people who constantly deny themselves of any pleasures and constantly put the needs of others before their own (compensation with the ‘Please me’ driver’).

Don’t relax or feel safe: This injunction I personally would perceive as being on a scale with two extremes. ‘Don’t relax’ can be viewed as the opposite of the ‘Work hard’ driver, and in this way is given as a message that it is not ok to take a break or rest. This might be a subset, as above, of ‘don’t be important’, as rest and recuperation are a basic need of everyone. Obviously, at this end, an adult with this injunction will demonstrate ‘work hard’ behaviour, but will also be nervous about appearing not to relax.

At the other extreme, ‘don’t feel safe’ would most likely form in abusive situations. This is formed out of extreme fear that the world and those around you are not safe. This message will be given by caregivers through threatening and fear inducing behaviours until the child believes that they no longer have the right or expectation to feel safe. The effects of abuse in adulthood are tremendous and exceptionally damaging. This is not the forum to cover these in detail. I will mention that two of the main effects in adulthood would be increased anxiety and depression. I would urge any readers who are aware of anyone, young or old who is expressing behaviours that suggest they do not feel safe, to please contact the relevant agencies and authorities, so that they can get help.

Don’t change: This is an interesting injunction which I would probably link to either ‘don’t grow up’ or ‘don’t be important’. The message being given to a child is that things as they are now, including you, are fine and should not change in any way. You can see how this is strongly linked to the message of ‘don’t grow’ up, which is that caregiver wants the child to remain helpless and needing their care (because the world is a difficult place). It could also be seen as a caregiver not wanting their child to grow I not just physical terms, but also competence. Again this might be because the parent has a fear of the unknown (in their child ego state). Therefore, they give the message to the child that they need to maintain the status quo, as the consequences of change will be terrible. In adulthood this would manifest as someone who resists change and perhaps seems to be stuck in a rut. Risk taking would definitely be out of the question, and they may become especially distressed should change happen unexpectedly.

Don’t be separate: This injunction is related to ‘don’t grow up’, but I think in a more extreme way. In some ways it is the opposite of ‘don’t be close’, however, that injunction is suggesting not be close to anyone. This injunction is suggesting not to be separate from specific people. It is related strongly to attachment issues (again something that I cannot go into detail here) and co-dependence. The message given to a child is that they are not a complete person, and that they must be “attached” to another in order to get their needs met. This ‘other’ would usually be a caregiver. They might be told that, “You are my everything”, or “really need you around”. The child feels that if they are not with this caregiver, providing company, support or other needs, that they are not worthy of getting their needs met. The relationship has become enmeshed and co-dependent. In adulthood, co-dependent relationship will develop with partners and then possibly their children. They will usually be clingy people, who require the input of others, and who do not feel complete without someone else. (A cliché is to think of a partner as being called, “my other half”, suggesting they are only half a person without them.)

I am aware that that discussion was exceptionally brief, and that each of those new injunctions was worthy of a post on its own. However, I feel that due to the complex nature of human interaction, and the fact that injunctions are rarely delivered in child in isolation, that there is a complexity to them that limits a complete breakdown (certainly not in a blog!)

So that is the injunctions and drivers of TA completed. In summary, drivers are messages delivered by caregivers in their controlling parent ego state and learnt by a child. They are instructions to perform certain behaviours in order to have worth. They were: Be strong, work hard, hurry up, please me, and be perfect. Often driver behaviours develop in response to injunctions which have been given, as they allow a person to maintain some form of worth through them. However, although drivers can be useful in some circumstances, they are extreme messages which cannot be lived up to or achieved. For example, it is impossible to be perfect. Therefore, the effects of drivers are ultimately negative and unhealthy when a person falls short of them, as this will leave them with a sense of failure and low self-worth.

Injunctions are messages that are delivered by caregivers, usually from their child ego states. They are perceived by children as restriction on what they are allowed to do. They therefore are always prefixed with “don’t”. The twelve main injunctions are, don’t: exist, do anything, be child, grow up, be you, succeed, be important, think, feel, belong, be close, be well. These messages are carried into adulthood and affect behaviours in negative ways. There are two responses to injunctions of defiant, in which case the opposite behaviour is shown (usually in negative free child) and despairing, where the restriction is strictly obeyed (usually from negative adapted child). As mentioned above, driver behaviour may be employed to compensate (I will discuss this in my next post). Injunctions can only be overcome when the child ego state is given permission to do this things that have been restricted. This permission is given from the person’s adult ego state. In a way, their adult is re-parenting their inner child from the past.

I hope this whistle stop tour of this aspect of TA has been of use. I will be moving onto a few more concepts in the coming weeks.

After a fair few months, we have arrived at my description of the last of the main injunctions from transactional analysis. They are all damaging in their own way, as I have outlined in my previous posts, but this last one is one of the more debilitating. It is the ‘don’t do anything’ injunction. Often this is abbreviated to simply ‘don’t’. Whereas the other injunctions are messages prohibiting specific behaviour (thinking, feeling, succeeding etc.), this one implies that all actions are to be ceased. There is some relation here to the ‘don’t exist’ injunction, in that by doing nothing, in a sense, you have ceased to exist as a causal agent in your own life. ‘Don’t exist’ often comes from the caregiver’s child ego state who is scared of the consequences for themselves or of their own inadequacies. ‘Don’t do anything’, I would suggest comes more from the caregiver’s child ego state being scared of the world in general.

‘Don’t’ as a message is often given to children when a parent is scared of the consequences of the child’s actions. It leads to the metaphorical ‘wrapping up in cotton wool’, where the child is seen as so fragile and pathetic that they need to be protected from all harm. The arguably modern phenomenon of the ‘helicopter parent’, perpetually hovering over a child to check where they are, who they are with, and being ready with an intervention, can be seen as a way of this message being delivered. The abbreviation to ‘don’t’ explains perfectly how explicitly this message is given to a child in an almost unceasing barrage of ‘don’t’ message. What follows the ‘don’t…’ can be anything. “Don’t touch that”, “don’t eat that”, “don’t talk to them”, “don’t say that”, “don’t ask” etc. These are all delivered from the negative controlling parent ego state. There is rarely an explanation for the reasons from the prohibition (which the adult ego state would provide), simply assertions that actions should not be done. There is usually an implicit understanding that the thing to be done is ‘bad’ or dangerous in some way. The child starts in this way to label things they do as ‘good’ and ‘bad’. This ‘don’t do anything’ injunction develops when the ‘bads’ far outweigh the goods. I unfortunately forget the source of the article, but I saw a headline which read, “What happens when we say “yes” to a child?” This headline speaks of how constantly telling someone no, will probably lead to that person giving up asking, and then giving up trying. These are both consequences of the ‘don’t’ injunction.

Implicitly, the message is also given by the caregiver’s negative nurturing parent, by never allowing the child to do anything for themselves. I have spoken before of the phenomenon of learnt helplessness. If a child never does anything for themselves, they never learn vital skills necessary for survival and resilience. They will literally do nothing and expect to be able to rely on others. This makes that person especially vulnerable when things go wrong, and ripe for exploitation by the unscrupulous. In extreme cases, narcissism may develop if the child gains a sense of self-importance and entitlement around the things that are given to him including attention and material things. It can be argued, however, that underneath narcissistic traits, there lies a vulnerability and fear of the world, and that the sense of worth held by the narcissist is false. Narcissism is a highly complex issue, and unfortunately this is not the correct forum for me to discuss my views on it further.

I have begum to outline the responses to this injunction already. In the despairing mode the child will believe the implicit message that they are incapable of doing things for themselves or defenceless to the trials and tribulations of the world around them. They will probably become quiet and withdrawn. Many of the traits of other injunction will be shown, for example, not expressing their opinions or feelings, acting in an immature fashion, sabotaging any successes they may have or not getting close to others. This will all be due to fear. Fear can lead to anxiety and depression, both of which are paralysing. This can be literal paralysis with the person not only unwilling to move and take an active part in the world, but also unable. It becomes safe not to do anything than to risk failure, pain or reprisals for attempting things. Withdrawal and risk aversion are common behaviours. One set of behaviour which may be missing are the driver responses. This is because they are employed to overcome something that is lacking in the person to try and regain a sense of worth. This inunction might lead someone to believe that trying anything is a worthless endeavour. So either all of the drivers will be tried (probably unsuccessfully) or none of them.

In the defiant position, the child may rebel against the message not to do things and so engage with everything possible. Some of the messages from the parent may be for safety, but if everything from the caregiver is a “no”, then which ones do you trust? Like the boy who cried wolf, the parent’s warning are not to be headed and risk taking can become established. Unfortunately, this stance is a vulnerable one, and due to the lack of explanation and teaching from the caregiver, it can be extremely difficult for the person to cope when the risks don’t pay off and things go wrong. Risk without resilience is a dangerous thing. I will also mention, that it might be that the ‘try hard’ driver may be employed in this position to counter the injunction that has been given. Remember however, that drivers set unrealistic aims which cannot usually be reached or maintained.

The main thing that people with this injunction need is the experience of having a positive nurturing and controlling parent, or an adult teacher to guide them. These states are able to provide encouragement (saying “yes”) and managed risk to allow someone to explore things safely. They learn with the person and allow them to try things out, with help if needed or on their own. They foster independence and resilience, not reliance and dependence. They promote self-worth through praising and valuing not just success, but also the learning from mistakes. In this way, I offer some permissions and messages that might be helpful when addressing this injunction:

The world is not an inherently dangerous place

People will help and support you, if you ask for it

Mistakes are the perfect way to learn

If you don’t try, you have already failed

You are a worthy and capable person

Skills can be learnt, things can be earnt. This may take time.

Life is not a series of “nos”. If you find that it is, tell yourself “yes”

The previous inunction was ‘Don’t think’, and so I thought it was only appropriate that this, the penultimate one should be ‘Don’t feel’. This inunction has major cultural implications, as it is formed from how parental figures handle and express their emotions. This is to a large extent embedded in our cultural heritage. I very general terms (and not wishing to perpetuate stereotypes or cause offence) different parts of the world express their emotions in different ways. For example, we think of people from South American countries as having a “Latin fire” and being passionate and unafraid to express strong emotions such as anger and lust. In many Arabic nations sadness and grief are expressed through wailing and self-flagellation, with the outpourings of their loss reaching near hysterical heights. We can probably think of nationalities who are portrayed (rather unfairly) as being emotionless, and robotic in their approach. In England, we are world renowned for our “stiff upper lip”. Not putting our emotions on display is cherished as a sign of strength and dignity. I would therefore, suggest that some nationalities are more susceptible (ours included) to the ‘don’t feel’ injunction than others.

As the name suggests, this injunction is about messages being received by a child that suggest having certain feelings or emotions is unacceptable, or makes them unworthy of love or attention. Just as the ‘don’t think’ injunction would judge certain thoughts, ideas, opinions or ways of thinking as being unacceptable, with this injunction, the same process occurs with emotions. From the caregiver’s child ego state, it is probable that some emotions are too scary or volatile for them to cope with. For example, for a caregiver that has suffered a bereavement, but they were unable to process their feelings of grief successfully, they may be unable to deal with sadness being displayed by their child. An adult that was unable to manage or come to terms with either their own anger or that of their parents, may not be able to cope if their child is angry. In this way, some emotions may be labelled as ‘good’ and others as ‘bad’. When I think of this assignment I am reminded of the Vulcan race from Star Trek. They have manged to purge from their psyches all emotions. While this might seem appealing, as it means we never have to feel things like sadness, disappointment, despair, jealousy, anger and the whole raft of unpleasant feelings, it does mean they miss out on the joy, happiness, love and wonderful emotions that living brings. Also, as the program sometimes shows, the Vulcan shave only repressed their emotions, with them sometimes boiling over into uncontrolled rage, or violent bouts of unbridled passion during their seven year mating cycle (pon farr).

A child with this injunction will learn that if they want the attention of their caregivers, they have to filter out all of the emotions that are not Ok, and only display the ones that are. Notice that I have said they can’t be displayed. That does not mean that the emotions are not being felt. They are being felt and judged internally by the child, thus making both them, and the emotion unacceptable. So messages that may be given include, “man up”, “big boys don’t cry”, “stop your bellyaching”, “stopping such an angry young lady!” and even “stop laughing so loud, you’ll disturb everyone”. You may have noticed in that list some gender links, as we have seen with previous injunctions. Again, this is generalised, but in many societies some emotions are acceptable for one gender and not the other, for example, anger is ok for boys and not girls, and sadness/crying is ok for girls and not boys. Also, no emotion is safe from exclusion. Some families find ‘excessive’ displays of happiness and joy to be intolerable. Others might find displays of love and affection to be too much. There are even some who try to deny all feelings at all. These very much follow the message of “Keep calm (emotionless) and carry on”. Of course, there will also be implicit ways of this message being delivered, either through behaviour towards the child displaying them such as ignoring them, punishing them or shaming them. It can also be learnt from the behaviour of the parent themselves. If a father for example only ever shows anger, and a mother sadness and disappointment, a child might think that these are the only emotions available. It is hard to know how to display things that we have never seen for ourselves.

So how might this injunction manifest itself as a child grows up? Well, from the defiant position, a child might become over-emotional, and appear to ‘play up’ I order to get attention from those around them that don’t appear to feel anything at all. This attention will usually be negative, but as I have mentioned before, any attention is better than none. As adult these people may seem overly dramatic or sensitive, reacting emotionally to anything and everything, perhaps appearing not to be able to regulate their emotions (which is probably true). From a despairing position, a child will label certain (or all) emotions as ‘bad’ and so therefore try hard not to display them, for fear of being rejected or punished. To express them, or even feel them will be taken as a personal sign that there is something wrong with them. This can have devastating effects on self-esteem. Repressed emotions also do not go away. Like a pressure cooker without a safety valve, they will find a way of leaking out, or be built up until they explode. As examples, anger might leak out as passive aggression, or sadness might get to a point that it leads to a breakdown.

This injunction also means that emotions which are unacceptable, might also be seen as un-survivable. What I mean by this is that a person gets stuck in immature ways of thinking about emotions, and so a bout of tears might lead to thinking that once they start crying, they may never be able to stop. Therefore, crying will be avoided at all costs. It will be seen as an insurmountable task to regulate, manage and soothe these terrible feelings. A set of covering up behaviours may also take place with one emotion being used to mask or be used instead of another. Anger is often used to cover up other feelings such as sadness, but excessive happiness can also be used (think of the cliché of the crying clown).

People with this injunction often need a lot of time and support to engage with their emotions in a healthy way. In some respects, they need time to learn how to express emotions, but also to recognise them and respond to them in a different way than fear. They will benefit from learning emotional literacy. This might involve them being able to name and then express their feelings. It could also mean being able to actually feel them, and stay with them in a safe and secure environment. Sometimes, mindfulness can be useful here, as it encourages us to be with our emotions in a non-judgemental way, but to also look at them holistically, for example linking them with bodily sensations. Counselling is a good place to try out and explore emotional literacy, and give yourself the permission to move away from a ‘don’t feel’ injunction. As before, I offer some permissions which may be useful in exploring and challenging this injunction:

Emotions are neither good, nor bad, it is how we respond to them that counts

It is ok and perfectly natural to feel different emotions

Feeling (happy, sad, angry, jealous, etc…) doesn’t make me a bad or flawed person, it makes me human

I am entitled to express how I feel, knowing I am not responsible for how another person responds

I am worthy of love and respect no matter how I feel at the time

Emotions are not permanent, and can be survived. I am capable enough to regulate and come out of an emotion safely

It is perfectly reasonable to ask for time to process my emotions. They can be complex and deserve time and respect (like me)

If I can’t name or express an emotion, that doesn’t mean I am not allowed to feel it